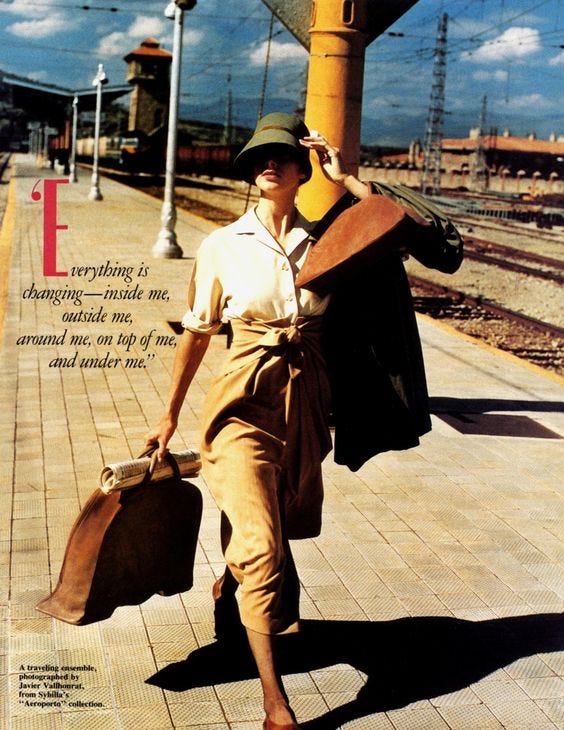

In 1989 Vanity fair interviewed Sybilla in Madrid just as she was on the cusp of signing with the Japanese conglomerate which would go on to drive her brand in the 90’s. This was a fraught and pivotal moment for her brands future expansion and to reread this interview now is to be both incredibly inspired by her immense creative drive and magical world, but also saddened at how this joy and creativity was ultimately dampened by the fashion machine.

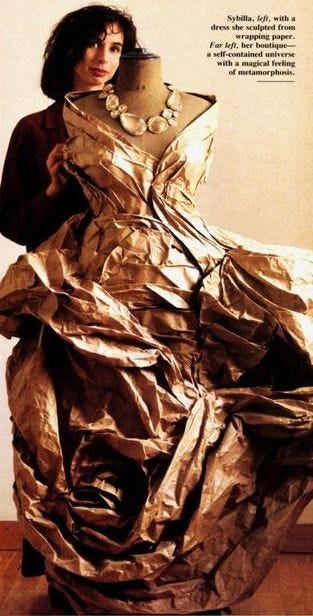

First a visit to her Madrid store circa 1989 at the height of her creativity, a space described as having a ‘sense of self contained universe governed by its own idiosyncratic logic’ with a ‘magical feeling of metamorphosis’.

The store was decorated with Moorish swirling wrought iron clothes racks hung with iron hangers which seem to have melted into Daliesque asymmetry. The iron fittings all the work of Kike Sirera, Sybilla’s ironsmith boyfriend.

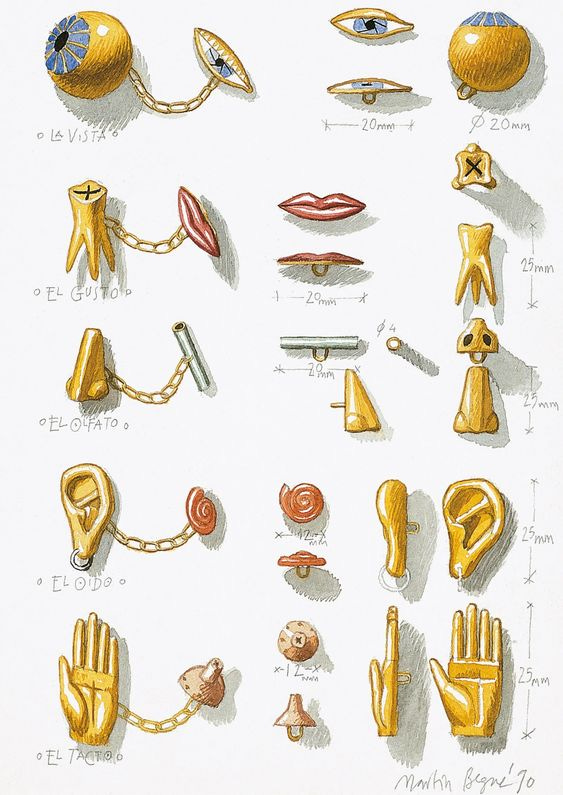

Simple muted coloured clothes reveal, upon inspection surprising details such as unexpected pleats or tiny sculpted buttons in the shapes of ears.

Sybilla’s ten member design and administration team are described as ‘all aged about 25….in forest toned Sybilla ensembles looking like an organic part of the shop itself.’

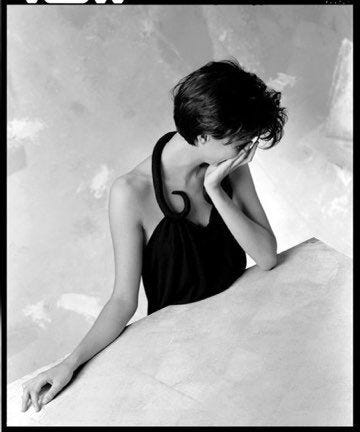

When speaking about her work and world Sybilla’s friends and associates tend to evoke the language of myth and folklore.

‘The dresses of Sybilla remind you of when you were a child and your Mother would tell you fairy stories - but in her dresses you live like that’

- Rossy de Palma (Actress and Sybilla model)

Cristobel, the sculptor who designed buttons and ornaments for Sybilla’s clothes sees analogies in the work of victorian fantasy artists Arthur Rachman and Richard Dadd.

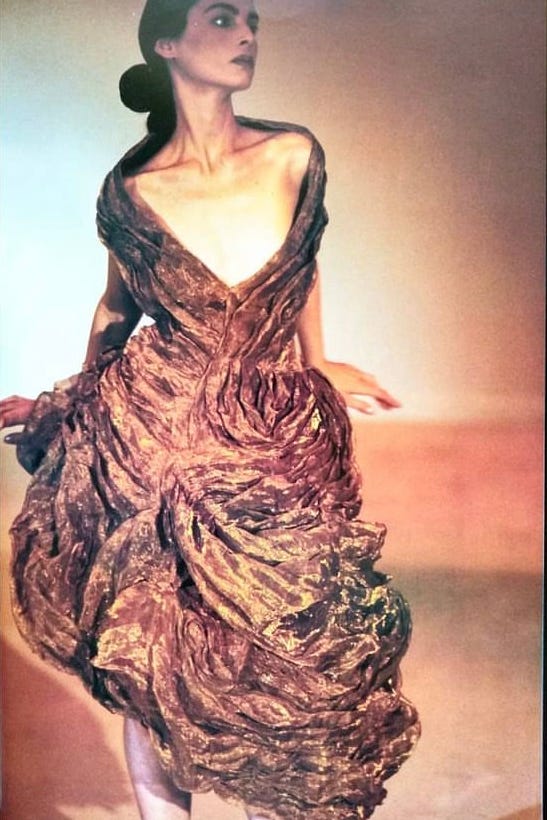

‘There are these crazy world around us, you never see them but they are there, like Bosch worlds and for me Sybilla’s clothes are of that world’

- Cristobel.

Sybilla is the the daughter of an Argentinean businessman and a Polish countess. Her parents met in Cairo, moved to Haiti then on to New York where Sybilla’s mother designed her own clothes for mass production. Finally they settled in Madrid when Sybilla was aged 7.

Due to her unusual family and upbringing Sybilla felt a sense of being different. At this time she describes herself as a pampered ‘enfant savage’ wearing psychadelic clothes and a wreath in her hair of snail shells. She had a vast menagerie of pets including dogs, cats, a fox, a goat and two porcupines. Her Mother who she describes as a very special character, had been known to awaken Sybilla in the night during a thunderstorm so she could feel the rain.

At age 14 her Mother died, triggering a rebellious phase in her life. She left school at 16 and managed to find a place as an intern at Yves Saint Laurent Couture in Paris. However she left this position feeling disenchanted with the cold commercialism of the business.

On Sybilla’s return to Madrid she took a job with a shoe manufacturer, a period she looks back on fondly.

‘They felt I was crazy, and I had all these extravagant ideas, they almost never used. But I was very young and very strong. I was ready to kill anyone to get my shoes done. I see that as my most creative period I think, when I had everything against me’

She began making clothes for private clients, curious friends would drop by and wound up sketching patterns for hats or assembling shoes. Apart from the seamstresses she hired, none of them had any knowledge of fashion (they all took starting salaries of less than $100 a month.)

Sybilla describes this period as one of ‘uninterupted work, of it being 1am and I am wanting to go to bed and my bed full of people talking.’ Sybilla had a network that included many artists that were associated with the La Movida Madrileña movement, you can see how they influenced each others work and they often collaborated.

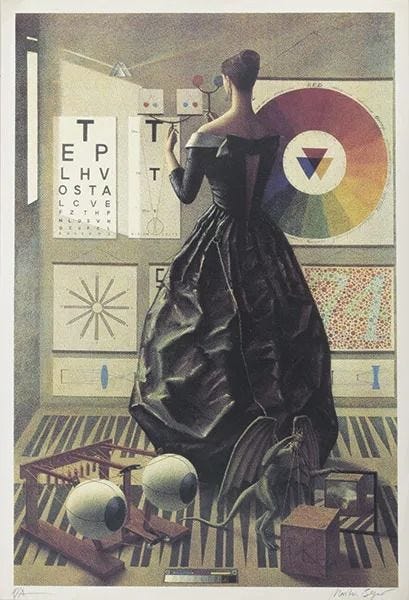

One of her friends, artist Sigfrido Martín Begué whose work hangs in her store (seen below), describes the Sybilla’s studio and home as a ‘nunnery’.

In 1985 Sybilla had an industrial backer, then in 1987 she switched to Gibo. Her shows during this period were quirkily tailored to showcase the personality of each model. She christened her first Milan collection - full of ensembles which were not what they seemed ‘Mantira’s’ (lies) because she found herself thrust into a fast dealing commercial structure where people were lying to her.

By 1989 Sybilla was worrying about the effects of having to concede to a more commercial structure - suddenly there was less space for spontaneity and ideas to develop. She was finding herself self conscious about her designs under the new pressure of her brands success, were they to commercial? or not commercial enough?

‘when there so much respect for my work, its like maybe I was much better when I worked in this little factory, where they thought i was absolutely crazy and I was drawing all day and people were laughing at my drawings.’

She wonders if she hasn’t built her own jail with her responsibilities.

In 1989 on the cusp of the Japanese deal the administrative team were happy -but for the design team it meant there would be change. At that time all the money Sybilla was making was going back into production, they had a separate person for the accessories, to make the buttons etc… its was all very expensive. They were optimistic -perhaps with the money brought in from the Japanese deal they will be able to do more of the things they want to do.

References -

Vanity Fair, November 1989, ‘Spain's New Flame’, Ben Brantley